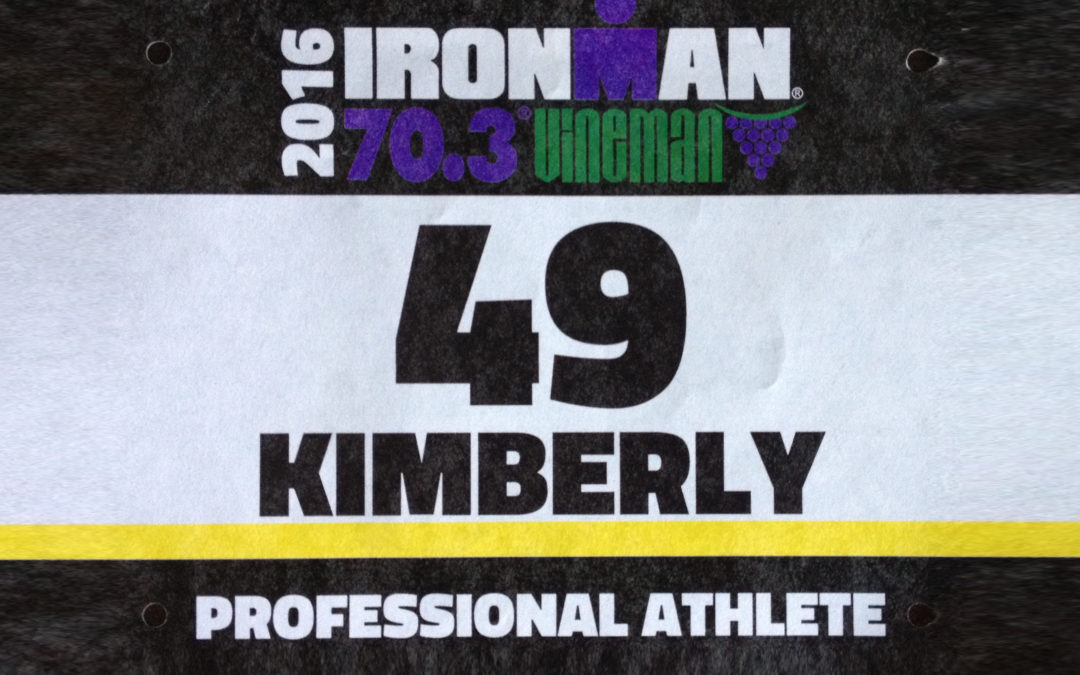

My pro card went into effect January 1, 2016, but for most of the season, nothing really changed. I raced some of the same local events I normally do, this time in a separate Elite category which usually put me in a field of one. Although I got to stand alone on the podium, first in my division, I wasn’t even really considered part of the overall stats anymore. I was set off to the side, almost as if I’d done a separate version of the race. They do things differently in the East & Midwest, so those races had cash prizes and a bigger Elite field, consisting of one or two other pro athletes and a handful of Elite Amateurs. But Ironman 70.3 Vineman was my debut into the real world of professional triathlon. The $50,000 prize purse brings in some of the top athletes in the world, and my name was thrown into the middle of a list published in a Triathlete.com article under the intimidating headline, “Impressive Pro Field Headed to 70.3 Vineman.”

Not everyone has supported my decision to move up to the Elite category. I’ve seen plenty of eyebrow raises from those who know all too well that you have to be extraordinarily talented and/or (but mostly and) have access to plenty of financial resources to actually make a living off of racing. The elite license allows access to the most competitive level of racing, but does not guarantee a paycheck as other professional sports do.

But that was never my objective in the first place.

As I considered the various reasons for going pro, winning my annual salary did not even rank in my top ten.

- Curiosity

- Greater challenges & tougher competition

- Preferred start times

- Discounted race entries

- Athlete homestays

- A possibility of meeting Jesse Thomas

- Street cred

- To give the women behind me their day on the podium

- A learning opportunity as a coach

- Make mom proud

But were those legitimate reasons to throw myself to the wolves? To step into an arena where I was so completely out of my league?

As I considered the reasons for not going pro, I came up with a list of only one:

- I’m not good enough.

And with that, my mind was made up.

Whether it is an old carryover from my low self esteem pre-teen years, or whether I’m simply the product of a society that encourages assumptions of inadequacy among women and girls, I’m done floating around in self-induced mediocrity. I was a smart teenager, yet I avoided the AP tests because they seemed too stressful and hard. And I didn’t apply to Berkeley or Stanford because I was pretty sure they’d reject me. I spent young adulthood languishing in dead end jobs, underpaid, under-recognized and passed over for promotions that I convinced myself I didn’t deserve anyway.

Triathlon is what delivered me out of this fog of doubt and inaction. Triathlon is where I’ve learned what kind of person I really am, and where I’ve encountered some of my most meaningful personal successes. But I also love this sport because it naturally attracts people who believe in overcoming adversity and breaking barriers, with role models like Sarah Reinertsen, Harriet Anderson and Karen Smyers.

Even if I never magically ascend the ranks of the super-elite like the underdog hero of a feel good sports movie, what message do I send to the women around me if I back down sheepishly and insist that I’m not good enough to even try? The amateur field at Age Group National Championships is stacked with sandbaggers who either used to be pro, or have already qualified and haven’t yet made the leap, or deliberately chose not to. There are plenty of good reasons not to, including career and family (although these are not mutually exclusive to pro racing, as Jackie Hering demonstrates so well), but I suspect that more than a few of these qualified women shy away from the opportunity because they are afraid. Afraid of not being good enough, afraid of crumbling under the pressure, afraid of trading in their predictable top podium spot for a view from the back of the pack. I agree with Kelly O’Mara’s assessment, that the best way to help women in the sport is to be one of the women in the sport.

So with my new mission to assist the advancement of women in triathlon, I marched forward into 2016 hoping my best days still lay ahead.

But I did not show up to Vineman 70.3 transformed into the new, improved version of myself that I had planned on. My training this year had not yet produced results that were significantly better than the prior year. And I had fought through the whole season ignoring a persistent foot injury. Maybe in some way, these elements took some of the pressure off. I knew I wasn’t ready to have the most amazing performance of my life. But it was time to face the terrifying truth – this was the real deal, these pro women were astoundingly skilled, and I could actually for real finish in last place.

So far, even though Elite status had been largely uneventful, I was beginning to feel a bit like a sitting duck. There were so many nuggets of pro knowledge that seemed impossible to search out. There is no Orientation Manual for new pros and I was walking through a minefield of rookie mistakes. At the Saturday mandatory pre-race meeting, the officials casually announced, “Water temp, at last measure, was 72.5 so of course it will very likely be a non-wetsuit swim…” He continued on, but my brain froze. Non-wetsuit?! With no prior warning? Neither the Athlete Guide nor the copious email updates regarding the event had made any mention of this possibility. I owned a skinsuit (which is the alternative when wetsuits are not allowed) but in 12 years of racing I had never needed it. And naturally, I hadn’t brought it on this trip. I was uber prepared for almost any scenario, with two pairs of goggles (for a sunny or a foggy morning) two spare swim caps (that I certainly wouldn’t need), two identical uniforms, and even two wetsuits (the sleeveless I had planned to wear, and a full length just in case the water was colder than predicted).

None of the other pros at the meeting reacted to the news. Apparently I was the only one in the room who hadn’t already considered that the water might be too warm.

This was a pretty serious crisis, since swimming without the skinsuit (or a wetsuit) results in significant loss of speed. With my swim speed standing as my least elite-worthy trait, I couldn’t afford any additional handicaps. I was already terrified of getting dropped by the entire field within the first four minutes of the race.

I frantically made a beeline for the Roka vendor tent at the expo, hoping that I could perhaps buy another. The sales assistant apologized, they hadn’t brought their collection of skinsuits this time around “since this race is wetsuit legal.” The temperature cutoff for pros is different than the cutoff for the general population, so the rest of the race participants were free to wear their wetsuits as usual.

Ultimately I lucked out and found one (literally one, in the correct size) at the Ironman store and tried not to think about how annoying it might be if the water temperature dropped overnight and the wetsuit ban was lifted by morning. All that stress for nothing, in addition to spending $215 on another skinsuit that would just gather dust in the closet, unused.

It turns out, I had nothing to worry about. When I arrived to the special pro transition area in the morning, I heard confirmation that wetsuits were still officially banned and I was relieved that I had gone ahead with the purchase.

I looked around our tidy little transition zone, lined with official looking placards displaying each athlete’s name and country, and I started laughing. Laughing at how unbelievable it was that I was actually here, with KIMBERLY GOODELL printed above the American flag. And laughing because sometimes that’s all I know how to do when a smile can’t contain my excitement.

I turned around and looked at the familiar names on the men’s side of the rack, names I’ve been seeing for years in all the triathlon publications. How many of these guys had been on magazine covers? My gaze met with a familiar looking face, one with the kind of bright enthusiasm that lights up a pre-dawn transition area as Andy Potts said, “Good Luck, Ladies!”

A little starstruck, I bubbled excitedly to Brad that he should watch for Andy Potts on the course, easily identifiable as the only male pro who actually looks like he’s enjoying the race. In fact, Brad was lucky enough to have front row seats to this spectacle:

Andy does not disappoint.

I’m in the pink cap.

Wave 2, at 6:30am, was the Pro Women, leading off 5 minutes after the Pro Men, and 10 minutes ahead of the 30-34 Women. I was surprised to find that I wasn’t appropriately nervous as we lined up for the deep water start. The wave was bigger than I anticipated, and somehow I felt safer in the group. Surely this would improve my chances of blending in. I didn’t mind being at the back of the pack, I just didn’t want to be in a completely different galaxy from the rest of the field. The starting horn blew, and a majority of the group predictably pulled away quickly. But I was in a small trailing pack, working hard, but staying right with them.

Four minutes into the race, I still had women behind me! I could finish this swim in not-last place!! I had quickly settled in behind one of my competitors, and I made it my mission to stay on her feet at all costs. She was giving me exactly the right kind of challenge – pushing me, but not quite to my breaking point. Periodically, I felt a hand brush against my feet, but no one pulled past me. A pro was drafting off of me! Hilarious.

This better-than-expected swim started my race off with the right tone. As I emerged from the water, snatched up my bike, and left at least 5 women in transition behind me, I felt like the day was already a success. It was a long haul to get from the pro section at the water’s edge, past the nearly 2,000 bikes in the age group transition area, and a cheer rose through the crowd as each of us passed through. Once on the course, I quickly overtook one woman, but then got passed by two. I just needed to make sure the rest stayed behind me.

After that, it would be another 40 miles before I would see anyone else. So I had the course to myself, and it certainly lived up to all the hype. The winding country roads and rolling vineyards were beautiful and serene, and I soaked it all in, loving every minute of it, tired legs and all.

It was in the final 10 miles when I began to see the first age groupers whizzing past. First, the Men 45-49, then to my dismay, an age group woman (the eventual Amateur Overall winner). She had closed a 10 minute gap on me! I hope to see her on the pro start line next year.

The day was shaping up to be pretty warm, and I had been amply warned about the un-shaded run course. I was hoping to avoid the leg cramps I had encountered in Wisconsin, so I was proactive with salt pills and plenty of hydration during my tour of the wine country. Thankfully, my quads did not cramp this time around, but they did morph into comic book superhero proportions as soon as I completed the bike. Though this is not my first encounter with this phenomenon, my He-Man Thigh is apparently not visible to the naked eye, as it only ever appears in race photographs.

The first 3-4 miles of the run had a few hills, and I was prepared for this chunk of the race to feel not-good. This prediction was spot-on, but I comforted myself with the notion that by default, this would mean the next few miles after that would surely feel good (as if such a thing were possible). But I did settle in to a nice rhythm, and with the roads and the vineyards to myself, I chugged along mile after mile. Just before Mile 8 a turnaround offered me a view of my closest competition in front and behind, and I was pleased with what I found. I did indeed have several pros a good distance behind me, so my goal of finishing not-last was easily within reach. But I had one other goal for this race, and that was to pass one person on the run. At Mile 8 I found her. She was some distance ahead of me, but once I could see her up ahead, the chase was on. I had 5 miles to close in. This is what I love and fear most about racing. I love it because the goal gives me focus. And I’m terrified of it because there is that ever present dark voice that says, “You can’t catch her. She’s just too fast. Look how far she is. Second Place is good enough (or Nineteenth Place, as it were)…”

When my feet are held to the fire, I have the option to double down or to fold, and I’m not always sure which it will be. But on this day, I felt strong and determined.

I may not be the fastest pro, but I’m definitely not the one that gives up.

I crept closer and closer, finally coming within arm’s reach of my competition as we slipped into the cone corridor leading down the final half mile of the course. I pulled even, running shoulder to shoulder with her, and dared her to push ahead, but she did not. So I made my move and kicked into high gear. Almost immediately I regretted it. Surely my surge was too much for me to sustain, surely she could see I was already fading back out. I should’ve waited longer! Now I had left myself wide open to a counterattack, the ball was in her court since she could see me and I couldn’t see her, and I was still an eternally long three minutes away from the finish line! I tried not to think about how devastating it would be to lose the position I had just spent 5 miles fighting for, in the final 50 meters of the race.

As I rounded the final corner, a volunteer steering us towards the finish called out, “GO GO! There’s a girl right behind you!”

In a grimacing panic, I willed my noodle legs to carry me just a little faster for a few more steps. I reached safety with an eight second lead, and then wobbled my way to the nearest shady patch of grass to collapse. How Andy Potts was able to launch himself straight up into the air at the finish line, I will never understand, but I guess that’s why those guys make the big bucks.